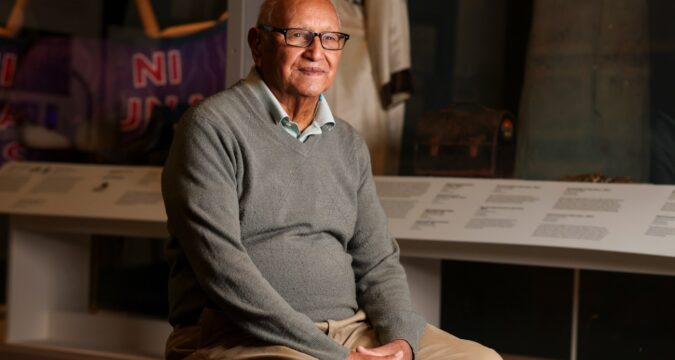

When 89-year-old Alfonso Quiroz saw his old workman’s lunchbox on display at the Chicago History Museum’s new “Aquí en Chicago” exhibit, he remembered his go-to lunch from more than a half-century ago: a ham sandwich, a banana and a thermos of coffee.

The former Pullman worker’s lunch pail is part of the exhibit that opens Saturday and showcases more than 170 years of Chicago’s Latino community in ways that go beyond addressing a history of insufficient representation.

Plans for the exhibit, presented in English and Spanish, were formed after high school students from Pilsen’s Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy protested the lack of Latino representation they encountered during a field trip to the museum in 2019.

The museum responded — by committing to doing better.

“The (students) noticed during their visit the inadequate representation for Latinos in the museum’s galleries,” said Jojo Galvan Mora, digital humanities fellow at the museum. “All they found were items that they thought were really problematic, like an ashtray in the shape of a sombrero from the … World’s Columbian Exposition … and they really felt like the museum wasn’t doing enough to represent their history, the history of what’s going on in the city.”

So the students came back and protested, demanding more representation.

“Aquí en Chicago” is more than just the museum’s response to those protests; it’s also part of a larger shift in how the museum tells stories and who is represented in the galleries, Mora said.

In fact, the protest posters used by the students are displayed on a wall as part of the exhibit. And Mora said several of the students — now in their 20s — also interned at the museum to help create the exhibit.

The result encompasses the deep history of Latino communities in Chicago, from a 2010 crown worn by the Cacica, or queen, at the Puerto Rican People’s Parade, to cowboy boots and a belt buckle from the famous Alcala’s Western Wear store in West Town, to an ice cream cart from Paleteria Reina de Sabores that traveled more than 100,000 miles during its tenure.

“Aquí en Chicago” also has interactive features where visitors can listen to house music created by local DJ and former Vocalo radio producer Jesse de la Pena, or hear a corrido, a traditional story song, by Jesus “Chuy” Negrete, whose guitar and case are on display.

While many of the displays are celebratory, some reflect more serious events in the community, such as the April 2020 Hilco demolition of a smokestack in Little Village that created a thick cloud of dust and debris that permeated the area, and the 2021 General Iron protests, an environmental justice and racial equity movement centered on the controversial relocation of a polluting metal shredder.

The exhibit also reflects longstanding tensions around immigration, including the Bracero Program, a guest worker initiative that brought hundreds of thousands of Mexican laborers to the United States during World War II and the following decades, and 1954’s Operation Wetback, a large-scale U.S. government deportation campaign that sought to expel undocumented Mexican immigrants, including some who had arrived legally through the Bracero Program.

“In this exhibition, we talk about so-called Mexican repatriation,” said Elena Gonzales, the museum’s curator of civic engagement and social justice. “Well, 2 million people were pushed out of the United States to Mexico during that time, and 60% of them were U.S. citizens. … Operation Wetback took place during the Bracero Program, when people were being brought here to work, and then at the same time, thousands of people were being expelled.”

Curator Elena Gonzales stands in front of students’ protest posters from 2019 in the “Aquí en Chicago” exhibition at the Chicago History Museum, Oct. 22, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Connecting the exhibit with the present-day targeting of immigrants by President Donald Trump’s administration, museum exhibition adviser Ester Trujillo sees mixed emotions in immigrant communities.

“We know that Latinos have been in Chicago for a very long time,” Trujillo said. “And there are these ebbs and flows of joy and pain. … What we wanted to do was to capture the core elements of that journey of historical presence and then also permanence.”

Trujillo said her favorite display features Quiroz’s lunchbox, apron and keys.

“My favorite part of it is the way it’s mounted, because when you look at the piece, you see a reflection, and it could be any of us wearing that apron,” she said. “Just looking at the stains and the weathering of the lunch pail, understanding that part of Chicago’s history is really interesting because it’s been here since the 1940s.”

The lunch pail, worker’s apron, and set of metal keys of former Pullman worker 89-year-old Alfonso Quiroz are on display in the “Aquí en Chicago,” exhibition at the Chicago History Museum on Wednesday, Oct. 22, 2025. (Eileen T. Meslar/Chicago Tribune)

Quiroz still lives in the Pullman neighborhood. He worked at Pullman-Standard from 1959 until the rail car manufacturing plant closed in 1981, and he gathered hundreds of items as they were being discarded at that time.

“The apron was made (of leftover fabric) from ripped up mattresses (on Pullman train cars),” said Quiroz, who started working there at age 23.

“I’m proud to be Mexican,” he said. “And I’m proud of the Mexican people who worked and lived in Pullman.”

Although the exhibit has been in the works for several years, Trujillo believes it is a gift to share it in this moment.

“It is bringing us together,” she said. “It’s a reminder that we’ve been here before. We’ve gone through this before. And we will get through it again.”

For Gonzales, it’s not hard to carry “Aquí en Chicago” beyond the Latino community.

“As we live through this moment in our history … no one should feel like this does not affect them,” she said, “because all of our rights are being threatened, and all of our rights are being erased by the current administration. We need to act in solidarity with that in mind.”

Mora wants viewers to leave “Aquí en Chicago” with a more comprehensive view of Latinos’ contributions to the city.

“More than anything, we want them to walk away with the understanding that the Chicago that we all know and love today is that way because of Latinos,” Mora said. “The Chicago that wins the award for best big city, for tourism, for everything, all of that is thanks to Latinos. Without this diversity, we lose that city. Latinos have always been here in Chicago, and they’ll continue to be. They’re resilient people. And that breadth of experiences that they bring make the city better.”

Trujillo noted that the exhibit is not just for Latinos. It’s for the entire city.

“I hope that people are able to see themselves represented in some way here,” she said. “Because we all have people who we know, people who we love, who probably have never seen themselves represented in an institution like the Chicago History Museum.”

Kelly Haramis is a freelance writer.

“Aqui en Chicago” runs through Nov. 8, 2026, at the Chicago History Museum, 1601 N. Clark St.; tickets $19 at chicagohistory.org

https://www.chicagotribune.com/2025/10/27/aqui-en-chicago-chicago-history-museum/