Renee Freer may never get the justice she and her family deserve after authorities say they closed the investigation into her killing without an arrest nearly 50 years after her head was bashed in with a rock in Monroe.

But what’s most disappointing for those who have ties to the case is that police believe they know exactly who killed her and have been told a statute of limitations issue and laws in place at the time involving the age of the suspect would make it impossible to make an arrest.

“It was crushing,” John Wasik, whose uncle was Renee’s grandfather, said of when the family learned there would not be an arrest. “It was unbelievable to me. I knew the case was coming to an end. I didn’t know what the ending would be.”

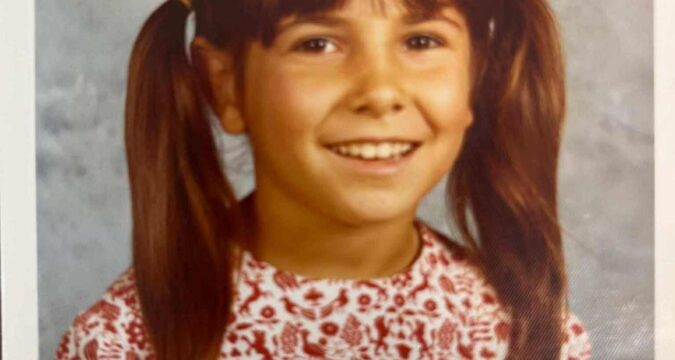

Police submitted an arrest warrant to the State’s Attorney’s Office seeking to charge someone in the death of Renee Freer, but they were told statute of limitations issues and the age of the suspect when the killing occurred led the warrant being denied. (Courtesy of the Facebook group “Who killed Renee Freer?”)

“This was not what I expected at all,” he said. “For 50 years we’ve been baited like a fish only to find out now about these laws. Is my cousin not worth anything? The murderer has more rights than my cousin?”

Renee was 8 years old when she was found dead on June 22, 1977, in the woods behind her family’s home on Williams Drive, which has since been renamed to Williams Road. She had gone outside to play after dinner and never returned home.

Her mother called for her to come inside before heading out to the grocery store to get ingredients to bake some treats for her daughter’s last day of the third grade, which was the following day. Assuming Renee was off playing in the neighborhood with other kids, as she often would do, Felicia Freer headed to the store.

Renee’s death led to a Facebook group devoted to sharing information that could lead to the arrest of her killer and inspired the book “Dead End Road.” (Courtesy of the Facebook group “Who killed Renee Freer?”)

It wasn’t until she returned home and Renee had not come back when her mother started to worry. She contacted police around 9:15 p.m., nearly three hours after the young girl had gone outside to play. A search then ensued in the woods behind the family home.

About an hour after police were called, Felicia Freer got the phone call that’s every parent’s worst nightmare. Her daughter was found dead in the woods after suffering blunt force trauma to her head. A rock next to her body was believed to be the murder weapon. Investigators did not find any signs of sexual assault.

The brutality of the killing left the community in shock, while also grieving the loss of such a young victim. Local police investigated extensively, seeking assistance from state troopers and the FBI before the case went cold.

After nearly 50 years, Renee Freer’s killer remains free. (Courtesy of the Facebook group “Who killed Renee Freer?”)

In recent years, police conducted a “full-scale re-examination of the evidence using new advancements in technology,” according to Keith White, chief of the Monroe Police Department. Investigators re-analyzed statements and re-interviewed several individuals.

“In the past 48 years, many people associated with this case have passed away or memories have faded, further complicating the investigation,” White said in a statement.

The case also garnered attention from the creation of the Facebook group “Who killed Renee Freer?” and the release of a book in 2024 entitled “Dead End Road.”

“A lot of momentum,” said Erik Hanson, the author, who used to live in Monroe. “We raised money — there’s a scholarship under Renee’s name — people put up a billboard. People were going to events, there’s been multiple podcasts, ‘Dateline’ wrote about it. It reached that level of attention after there was nothing written about it since the late ’90s.”

The attention brought renewed hope that police could finally charge Renee’s killer. Investigators were closer than they had ever been when they submitted a juvenile arrest warrant to the Bridgeport State’s Attorney’s Office on July 11, according to White. The warrant sought to charge a man, who was under 14 at the time of the killing, with first-degree manslaughter.

A little more than two months later, “after careful consideration,” police received word on Sept. 18 that prosecutors did not approve the warrant, White said. Police were told that prosecution on a manslaughter charge was subject to a five-year statute of limitations.

And because the suspect was so young when Renee was killed, the law at the time prevents authorities from now seeking a murder charge, according to White.

“At the time of the crime, under the Connecticut General Statutes, a juvenile charged with murder could only be transferred to the regular criminal docket of the Superior Court provided the juvenile suspect was at least 14 years old when the murder was committed,” White said.

White acknowledged that Renee’s murder over several decades has “had a tremendous impact” on Renee’s family, friends, residents of the town and beyond and all the investigators who worked tirelessly on the case.

“Nonetheless, given the current status of the investigation and the conclusive opinion of the state’s attorney, this case has regretfully been marked as closed,” White said.

The news was beyond devastating for those who pushed to finally see Renee’s killer brought to justice.

“This is so wrong on so many levels,” Wasik said. “It’s just unbelievable to me and to my family as well, and the police that have put the work into it. I mean, words really can’t describe how I feel.”

Wasik said his family was always led to believe justice was obtainable despite the age of the case.

“Otherwise, why would they be investigating?” Wasik asked. “What would be the purpose of all this work put in if it was going to lead to nothing?”

“That’s ridiculous,” Wasik continued. “Did you just find this out? This was 1977 when it happened. I just don’t understand how we get here — where it’s just completely over.

“The part that’s particularly difficult for those involved to accept is why police weren’t told sooner that the age of the case and the suspect essentially left an arrest out of the question. That’s what’s lost on me. Why were you considering this?” Hanson asked. “Because, quite frankly, this result could have been decided 30 years ago.”

When asked for comment, a spokesperson for the Connecticut Division of Criminal Justice said the State’s Attorney’s Office could not provide specifics.

“In accordance with current law and the ethical obligations that govern prosecutorial conduct, the Bridgeport State’s Attorney’s Office is not in a position to comment publicly on the specifics of this case at this time,” the spokesperson said.

Accepting that the case was closed without an arrest was even more difficult after feeling like authorities were so close.

“It’s renewed hope and that there are people connected to the family that really want this,” Hanson said. “So they had all that new hope with all the attention and it just turns into a rejection. Everyone gives up, he gets away. Yeah, it’s pretty, that’s pretty horrible. It’s beyond awful.”

Hanson has called on members of the Facebook group to make calls to the State’s Attorney’s Office, but he acknowledged that there are long odds that anything will come of it.

“They know who did it,” he said. “People know who did it. That guy could probably walk right in front of the Monroe Police Department today and say he did it and dance in front of the whole station, but they just closed the case. I do not understand that.”

Though it may look dreary, Wasik said he’s not giving up. He’s hopeful a law firm or advocacy group will come forward and offer to help take a look at the case to determine if anything can be done.

“That’s what I’m hoping, that somebody will come along to help us,” he said.

Even if the family never sees a conviction, Wasik said he wants the man responsible to have to face the music in court.

“I was looking to bring him into court so everybody would know who did it,” he said.

“The important thing was to get him into court so that everybody knew — all his friends, his family, whoever he works with — everybody would know who he was and what he did and why,” Wasik said. “Instead, he gets to walk.”